|

|

|||||

|

<< September

<< July/August

<< July/August

<< September

<< Nov/Dec 2014

<< June

<< June

<< Part I

(June/July)

<< June

<< June

<< June

<< Part I

(June/July)

* * * |

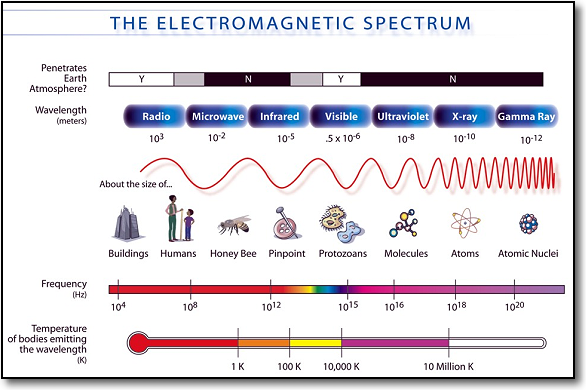

An "Illuminating" Subject . . .The Science of Light and Optics, Part I With the first stop of this years World's Fair Express in Paris, also known as the City of Light, it seemed fitting to devote a segment of the 2014 essay section to the subject of light. The August and September essays will be a two-part discussion of some of the many aspects of light - from basic scientific principles to some of the many products and technologies resulting from the application of those principles. Given that this is the summer of "S.T.E.A.M" as well, the discussion will include a focus not only on the scientific and technological aspects but also light as related to art, including photography (the word photography is derived from Greek words meaning "light" and "to draw or to write.") The pieces are not written for experts in the field (though experts are more than welcome to forward comments if they feel that any vital information has been overlooked). They are written, however, with the hope that any of the many students heading back to class over the next month or so who come across the page may find the subject interesting enough to pursue further research on their own. As with past editions, the essay also is "interactive." Links to other websites or videos which expand upon the topics being presented are embedded at various points in the article. By clicking the links viewers can read or see more about the particular topic being discussed, then return to the essay. Footnotes and a bibliography also are included at the end for anyone wishing to learn more about the subject(s) discussed. The materials represented here are only a small fraction of what is available on the subject matter. The subject of light has fascinated humans for thousands of years, from early questions about how we see and perceive, to the use of light to capture images and view distant phenomena. The lexicon of light crosses boundaries of science, technology, commerce and art, from the moniker for Broadway as the Great White Way (derived from the brilliant blue white lights installed between 14th and 34th Streets in the 1880s (n1)) to terms like "limelight." (Theater companies once lit stages with strong beams of light produced by putting lime [calcium oxide] in a flame generated by burning hydrogen and oxygen gases, hence a word meaning the spotlight of attention. (n2)) This summer's journey on the World's Fair Express begins in the City of Light, Paris, in the late 1800s, so it is perhaps an apt time and location from which to begin a discussion on the subject of light. The event took place in an era not unlike that of today - one of significant scientific discovery as well as commercial and artistic growth and development. By the late 1880s the principles of photosynthesis and the importance of the sun's light to life on earth were understood, and many of light's natural properties had been explained or theorized. The 1887 discovery of the photoelectric effect by Heinrich Hertz paved the way for Albert Einstein's 1905 explanation of photons as the basis for that photoelectric effect, bringing about a more complete understanding of the properties of light and earning Einstein a Nobel Prize in physics. At about the same time, the race to bring electric power to the U.S., extending natural daylight with man-made electric light, also had begun. Arc lamps, incandescent lamps and transformers all came into existence in the late 1800s, as did the "War of Currents" pitting Edison's low-voltage direct current (DC) systems against the higher voltage alternating current (AC) systems of Nikola Tesla and Westinghouse. It was at the next stop on the World's Fair Express, the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, that the "War of Currents" was (for the most part) won. The contract for lighting the Exposition, the world's first all-electric fair, was awarded to Westinghouse (working with Tesla) over Edison. Author Jill Jonnes, in her book Empires of Light, includes the following passage about the Chicago Columbian Exposition: " . . . Just four years earlier, the 1889 Paris Exposition had used 1,150 arc lights and 10,000 incandescent lamps; the Chicago Exposition had ten times that number in its buildings and grounds . . . By the time the fair was fully opened and up and running, the Westinghouse Electric Company had installed almost triple the number of lights - 250,000 "stopper" bulbs - called for in the original contract . . . Many motors were run also. The nerve center for this biggest of AC central stations was the highly visible Westinghouse switchboard in Machinery Hall, the control panel monitoring the 15,000 horsepower of electricity flashing out to the fair. The switchboard, made out of (noncombustible) marble, was a hundred feet long, ten feet high and divided into three sections . . . Here, finally, at the World's Fair, George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla could beguile the American public with their dream of cheap power, sketching outlines of the radiant electrical world taking shape, where electricity was cheap and universal, changing forever - in ways almost too momentous to imagine - how people managed the physical world, how they spent their evening hours, the very nature of work and leisure." (n3) The lighting viewed by the millions of people who visited the Chicago Exposition allowed them to see first-hand the benefits of Westinghouse/Tesla's AC power. In the online text of a PBS program detailing Tesla's life and legacy, it was noted that "from that point forward more than 80 percent of all the electrical devices ordered in the United States were for alternating current." (n4) The "War of the Currents" had been won. The technology of "drawing or writing with light," or photography, also was undergoing rapid advances during this period. Introduced in 1839, the Daguerrotype was for many years the most widely-used photographic process, though it was followed quickly by advances in lenses, cameras, film and development processes. In the early days of photography, images were considered more as an extension of science than as works of art, a relationship which "was vigourously debated for the better part of the century." (n5) "For those who felt that photography merely replicated nature rather than translating or interpreting it [the job of art], science was photography's only appropriate application . . . Others took a less hard-line view of the medium and viewed the representational status of the photo in a somewhat more generous way, dubbing it an 'art-science' and acknowledging the ambiguity that such a hybrid category connotes." (n6) An exhibit of photographs at the first World's Fair in London in 1851 contained, among other things, one of the first successful Daguerrotypes of the moon taken through a telescope, and by the Paris Exposition of 1889, the photography display at the fair was extensive, as pictured below. "Photography Exhibit, Palace of Liberal Arts, Paris Exposition, 1889." Photo courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress. By 1889, photography had already become both an accepted and recognized format for documenting images for science, as well as a nascent format for art. The first mass-marketed camera, the Kodak No. 1, was introduced just one year prior to the Paris Exposition and sold "for $25 . . . The entire camera [was] returned for processing to Kodak where the film [was] developed and printed and the camera reloaded with new film." (n7) One author points to three factors which contributed to photography's gradual acceptance as an art form as well as a means of visually recording scientific information during that period. Those three factors were a change in tastes among artists "reject[ing] the old historical themes for new subjects dealing with mundane events in contemporary life, . . . the change in [forms of aristocratic] art patronage and the emergence of a large new audience for pictoral images . . . [especially] immediately comprehensible images in a variety of diverting subjects, and [the opening of a market for] . . . graphic images designed to satisfy middle-class cravings for instructive and entertaining pictures." (n8) Those "entertaining pictures" also included ones made with X-rays after their discovery by Conrad Rontgen in 1895. The images fascinated not only scientists but the public, who at the time saw the images not as "medical diagnoses waiting to be made or data to be deciphered, but rather [as] spectacular glimpses into realms normally opaque to human vision." (n9) Which brings the discussion back to what most people normally associate with light - what they can see. But visible light is only one small portion of "light" in its broadest sense. Early explorations of the subject of light were followed in the early- and mid-20th century by the discovery and/or use of radar, lasers, and holography. Today, "optics" - related fields of science and engineering encompassing the physical phenomena and technologies associated with the generation, transmission, manipulation, detection and utilization of light (n10) - includes all of the following and more: radars and radar-evading stealth technology, infrared detection and microwave radiation, lasers, fiber optics, holography, cell phones, photovoltaic cells and solar energy, medical diagnostics and medical treatments, cameras, telescopes, microscopes, information storage technology and inter-planetary exploration. In the spirit of S.T.E.M., this section will continue by examining some of the basic scientific principles of light. Part II of the series in September will continue with a look at applications for optics, including those applications relevant to the arts. A good starting point for understanding light begins with understanding the Electromagnetic Spectrum. The Electromagnetic Spectrum and Basic Properties of Light For many years the question of "What is light?" puzzled scientists. Is light a wave? Is it a particle? Experiments and demonstrations in the late 1800s to early 1900s provided the proof of light's dual nature as both a particle and a wave, something which to this day is not fully understood. (n11) As outlined by Einstein, light as a particle is composed of "tiny packets of energy called photons . . . A single photon of one color (or wavelength . . .) differs from another photon only by its energy." (n12) Light as electromagnetic radiation, or waves, is depicted in the chart below, going from lower energy, lower frequency and greater wavelength radio waves on the left, to higher energy, higher frequency and smaller wavelength gamma rays on the right. As illustrated on the diagram, visible light forms only a very small segment at the middle of the spectrum and is divided into six colors - red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet. The higher energy portion of the spectrum immediately to the right of violet is called ultraviolet (ultra meaning above or beyond), and the lower energy portion of the spectrum to the left of red is called infrared (infra meaning lesser or below).

The Electromagnetic Spectrum. Image credit: NASA. Available online at http://mynasadata.larc.nasa.gov/science-processes/electromagnetic-diagram. One author suggests that in thinking about light as a wave or a particle, it may be useful to refer to a particular part of the spectrum pictured above. "For example, radio waves seem to be more intuitive than radio particles or rays. On the other hand, gamma rays or x-rays make more sense than "x-waves." This is just a simple reference to the energy of the light. At the highest energies, it seems easier to think of light as a particle: singular, penetrating, exact. At the lowest energies, it is easier to think of it as a wave: long, undulating and pervasive." (n13) Also, the higher energy rays such as gamma rays and x-rays emanating from outer space are prevented from harming human life since they are not able to penetrate the earth's atmosphere. Visible light and low energy radio waves are primarily the two types of light able to penetrate the earth's atmosphere. Those wishing to understand the concept of photons and particles of light might want to visit the July 2010 essay on the conversion of solar energy to electric energy in photovoltaic (solar) cells. Other more general tutorials on light and cameras can be found at http://science.howstuffworks.com/light.htm and http://electronics.howstuffworks.com/camera.htm. Some other properties of light necessary for understanding the basis of optics include: -- The human eye can only see light coming directly from an energy source like the sun or a light bulb, or light which is reflected from a surface. One example of a type of light which was created by harnessing some of the properties of light mentioned above is a laser. The word laser stands for Light Amplification by Stiumulated Emission of Radiation. The laser was first developed in 1960 by Dr. Theodore Maiman of the Hughes Research Laboratory in California, and in a relatively short time the laser has become an important component of everything from grocery bar code scanners to surgical tools. The development of the laser took into account both the particle and wave properties of light and added stimulation and amplification to create an intense narrow beam of coherent light (n15) (light which doesn't spread out like the beam emanting from a headlight or flashlight) which can travel a few inches to hundreds of miles or more. The following is a general but slightly more technical description of how a laser works: "Lasers work by enclosing a material, called the medium, in a cavity [such as a tube] between two polished, reflective surfaces. The medium contains the atoms or molecules that emit . . . photons. Energy from some source such as an intense light invigorates the medium . . . A single photon in the cavity eventually grows to a large collection of photons, all with identical properties - they are in phase and move in the same direction . . . The energy is needed because the particles of the medium must be kept in an excited (energetic) state. Substances normally exist in a low-energy state, where only a few atoms have enough energy to emit photons . . . The energy pumped into the medium results in a population inversion: Most of the particles are in an excited state rather than a low-energy state, an inversion of the typical situation . . . The product of a laser is coherent light because the stimulated photons stay locked in step with each other, acting like a single "wave." The polished surfaces enclosing the laser medium act as mirrors, and the photons bounce back and forth until a sufficient number have accumulated. One of the surfaces is only a partial mirror, so eventually the amplified light can escape the cavity." (n16) To make the concept of coherent light more understandable, it has been compared to the difference between a crowd and a marching band exiting a stadium. The crowd disperses in all directions (like regular light) but a beam of coherent light moves like a marching band exiting in unison, marching together in lock step and at the same speed. (n17) Some of the many uses of lasers will be discussed in the second segment of the essay in September.

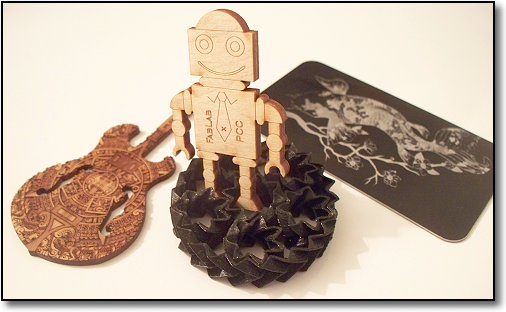

Locally from lasers and 3D printers: At far left is a laser-cut guitar made from a very thin piece of wood by EpilogLaser earlier this year during a demonstration at the Family Day at the Beall Center for Art and Technology at UC Irvine. The other three items are from a spring open house at the new Fabrication Laboratory (FabLab) at Pasadena City College (PCC). The laser-cut wooden robot, laser-etched koi-pattern card and 3D-printed plastic gear/wheel were all made on machines at the Lab. The Lab offers hands-on experience in 2D and 3D design, photo imaging and video production, laser cutting, 3D scanning and printing, wearable technology and robotics for those wishing to explore a variety of design, media and technology-related careers. It was said above that in a very short time lasers have come to be important components of everything from grocery store bar code scanners to surgical tools. In these and other products they are enabling technologies, elements or components of the successful operaton of a larger system. A lens is the optical component of a camera, along with its other mechanical (and in the case of film, chemical) components. "A compact disk player incorporates hundreds of intricate electronic and mechanical parts, all working together and all absolutely dependent on a single laser costing less than a dollar to illuminate the spinning disk." (n18) The same can be said of optical components in hundreds of other products. The "breadth of optics' enabling role is both an indicator of the field's importance and a source of challenges. Virtually every scientific discipline uses optics in some way, so . . . optics courses in most universities are taught in several science departments, as well as engineering departments and schools of medicine . . . Optics is thus . . . a field often seamlessly integrated with electronics and materials science . . . and an enabling presence in the university research lab, in our daily lives, and in countless businesses." (n19) Come back in September for Part II of "An Illuminating Subject" to learn more about optics and some of the field's many applications in products both familiar and new.

FOOTNOTES - The footnotes are indicated in the text in parentheses with the letter "n" and a number. If you click the asterisk at the end of the footnote, it will take you back to the paragraph in which the citation was located. n1 - Jonnes, Jill, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse and the Race to Electify the World, New York: Random House, 2003, p. 79 (*) n2 - Kirkland, Kyle, Light and Optics, New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2007, p. 127 (*) n3 - Jonnes, Empires of Light, pp. 265 and 268 (*) n4 - Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), "Tesla: Life and Legacy - War of the Currents," online program text viewed August 2014 at http://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_warcur.html(*) n5 - Keller, Corey, editor, Brought to Light: Photography and the Invisible, 1840 - 1900, San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2008, p. 22 (*) n7 - Hoy, Anne H., The Book of Photography: The History, The Technique, The Art, The Future," Washington, D.C.: The National Geographic Society, 2005, p. 428 (*) n8 - Rosenblum, Naomi, A World History of Photography, 3rd Edition, New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1997, p. 16 (*) n9 - Keller, Corey, editor, Brought to Light, p. 73+ Plates/X-rays (*) n10 - Committee on Optical Science and Engineering, Board on Physics and Astronomy, National Materials Advisory Board, Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics and Applications, and Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems of the National Research Council, Harnessing Light: Optical Sciences and Engineering for the 21st Century, Washington D.C.: National Academies Press, 1998, p. 5 (*) n11 - Kirkland, Kyle, Light and Optics, p. 9 (*) n12 - Beeson, Steven and Mayer, James W., Patterns of Light: Chasing the Spectrum from Aristotle to LEDs, Washington D.C.: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2008, p. 80 (*) n14 - National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Optics: Light, Color and Their Uses: An Educator's Guide with Activities in Science and Mathematics, EG-2000-10-64-MSFC, Huntsville, AL: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, 2000, pp. 3-10 (*) n15 - Quimby, Richard S., Photonics and Lasers: An Introduction, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2006, p. 281 (*) n16 - Kirkland, Kyle, Light and Optics, pp. 66 - 68 (*) n17 - Berger, Melvin, Lights, Lenses and Lasers, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1987, p. 47 (*) n18 - Committee on Optical Science, et. al/National Academies, Harnessing Light, p. 6 (*) LINKS LIST - The list of links external to the website found in the essay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY - The bibliography for the "Illuminating Subject" essays will be a joint bibliography included with the September essay. To return to the top of the page, click here. To return to the essay archives, click here.

Follow www.dorothyswebsite.org on TWITTER! Home |

Essays | Poetry | Free Concerts | Links | 2019 Extras |

About the Site |

||||

|

www.dorothyswebsite.org © 2003 - 2019 Dorothy A. Birsic. All rights reserved. Comments? Questions? Send an e-mail to: information@dorothyswebsite.org | |||||

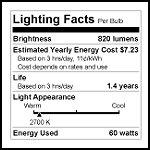

In order to help consumers better understand the lighting products they are purchasing, all light bulb packages are

now sold with a "Lighting Facts" label such as the one pictured here. One of the biggest changes in making a selection of the newer, more energy-efficient bulbs, is the measure of a bulb's brightness. Before, consumers made a purchase based on watts (how much energy a bulb used), such as a 60W, 75W or 100W. Now the standard

measure is brightness, as described on the new labels in lumens. The FTC describes the difference on one of their consumer information pages as follows. "A standard 60-watt incandescent bulb, for example, produces about 800 lumens of light. By comparison, a CFL bulb produces that same 800 lumens using less than 15 watts."

In order to help consumers better understand the lighting products they are purchasing, all light bulb packages are

now sold with a "Lighting Facts" label such as the one pictured here. One of the biggest changes in making a selection of the newer, more energy-efficient bulbs, is the measure of a bulb's brightness. Before, consumers made a purchase based on watts (how much energy a bulb used), such as a 60W, 75W or 100W. Now the standard

measure is brightness, as described on the new labels in lumens. The FTC describes the difference on one of their consumer information pages as follows. "A standard 60-watt incandescent bulb, for example, produces about 800 lumens of light. By comparison, a CFL bulb produces that same 800 lumens using less than 15 watts."